Mantel’s Research Process for the Wolf Hall Series

Emma Anderson - Peter Harrington Rare Books

“It is the place we put the tip of our knife, to drive them apart.”

At Wolf Hall Weekend we’re always on the lookout for pieces that slow us down and let us look more closely at how Hilary Mantel actually worked — the thinking and patient accumulation of detail that made her brilliant work possible. This piece by Emma Anderson first appeared on the Peter Harrington Rare Books blog, it offers exactly the kind of insight we relish: Mantel at her desk, surrounded by sources, turning scholarship into sentences that feel inevitable once you read them — yet could only have been arrived at through years of immersion.

We’re very grateful to Peter Harrington Rare Books and to Emma Anderson for generously allowing us to repost the article here, especially as it offers a rare glimpse into Mantel’s relationship with Mary Robertson, to whom Hilary dedicated all three books in the Wolf Hall Trilogy and who is now retired from the Huntington Library - the home of Mantel’s archive.

***

Emma Anderson - Peter Harrington Rare Books

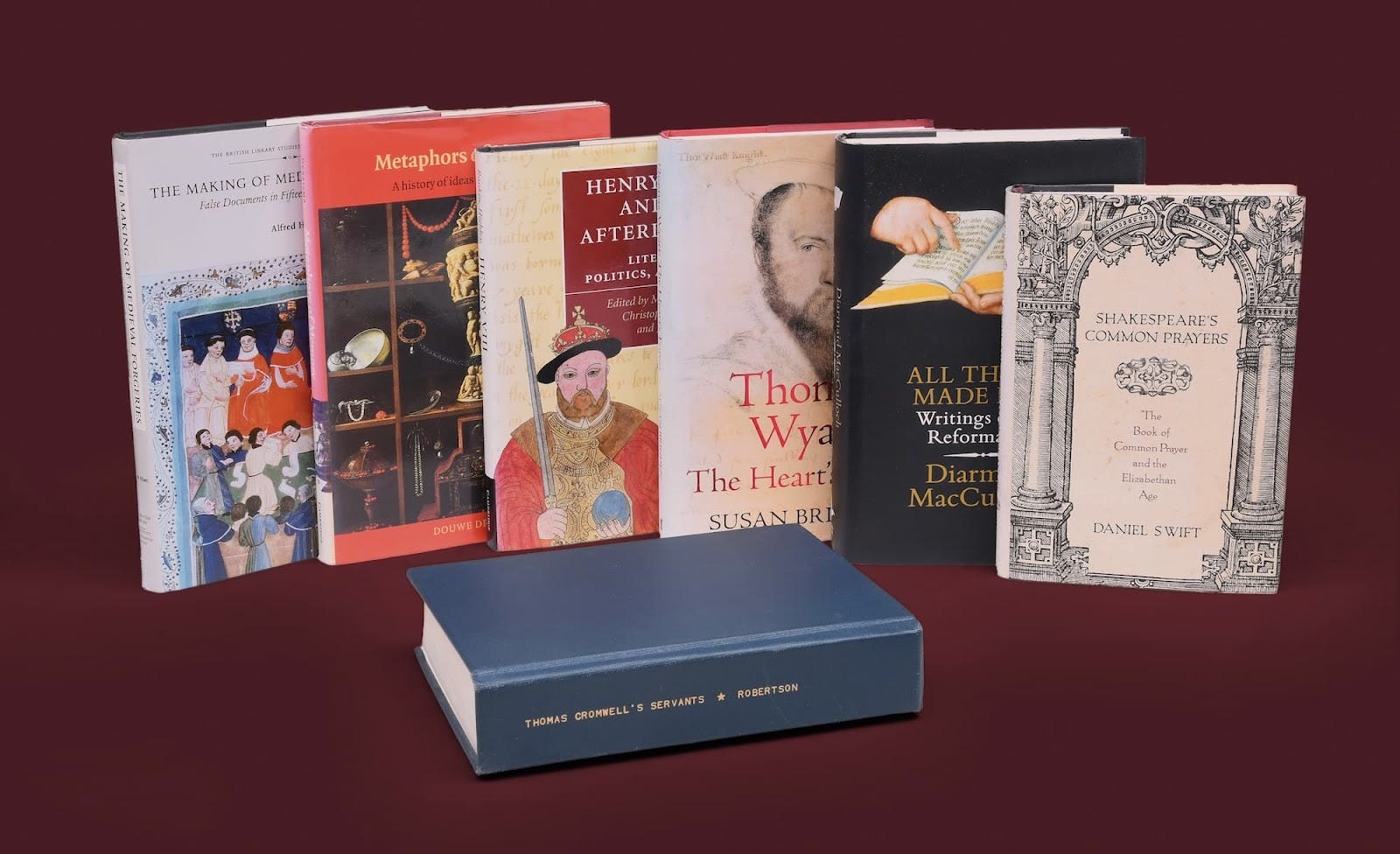

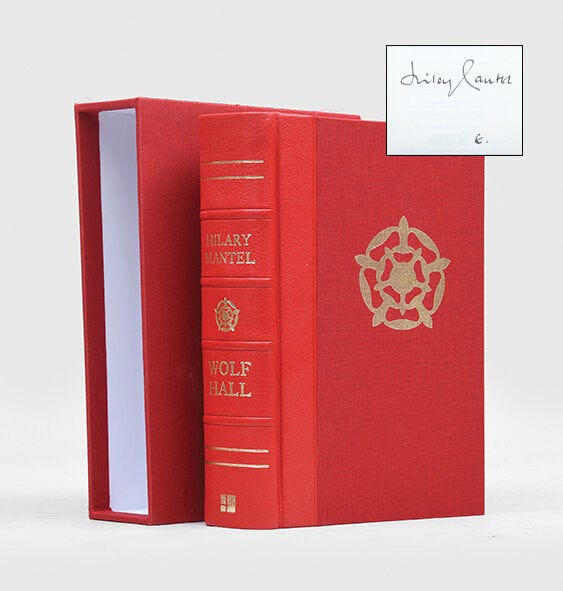

Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall series was a landmark in modern literature. Not only did it reform Thomas Cromwell’s public image, but it increased the literary status of the entire genre of historical fiction: Wolf Hall was the first book of the genre to win the Booker Prize and Bring up the Bodies was the second. The series’ reputation owes much to Mantel’s historical accuracy, developed over many years of study of the Tudor period. I leapt at the opportunity to catalogue this collection of her research materials, as I knew it would provide insight into the process by which Mantel crafted the books.

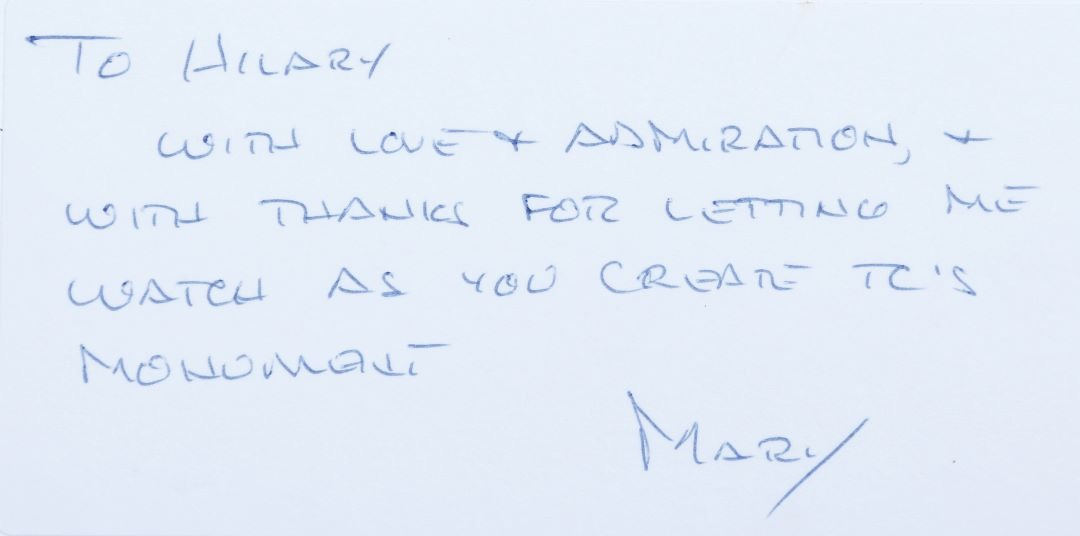

The centrepiece of this collection is a copy of a PhD dissertation by Dr Mary Robertson titled Thomas Cromwell’s Servants: The Ministerial Household in Early Tudor Government and Society. Mantel met Robertson in 2005 when she was giving a talk at the Huntington Library, California, where Robertson was the Curator of British Historical Manuscripts. The two women were introduced after Mantel mentioned to one of Robertson’s colleagues that she was planning a book on Cromwell. Robertson sent Mantel one of her limited copies of her dissertation, sparking a correspondence described by Mantel as “luminous” (Simpson), in which Mantel “mined for information and followed up with questions about Cromwell” (Robson). Robertson and Mantel became close friends and acknowledged one another’s work: Robertson inscribed her dissertation, “With thanks for letting me watch as you create TC’s monument”, and Mantel dedicated each book of the trilogy to Robertson.

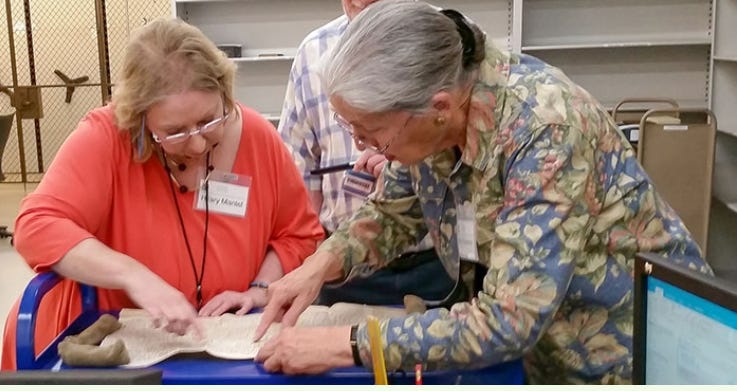

In 2010 at The Huntington, Hilary Mantel (left) and Mary Robertson pored over a parchment legal document bearing Thomas Cromwell’s signature, Photo by Sue Hodson. | The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

When reading Roberston’s dissertation, the inspiration Mantel took from it is evident. Robertson’s particular focus, along with Cromwell himself, are the individuals that comprised his ministerial household, such as Rafe Sadler, Thomas Wriothesley, and Richard Cromwell. Like many wealthy men of his era, Cromwell accepted young men into his household, where they would learn clerical, legal, and political skills, in exchange for their service and loyalty; they were effectively live-in civil servants. Major regime change of the kind initiated by Cromwell was dependent on the administrative and legislative work of such individuals, but they are rarely included in popular history discourse or in historical fiction. Mantel, on the other hand, affords Cromwell’s aides their full influence. She depicts Cromwell as almost constantly surrounded by them, and they are shown to have direct influence over his fortune as it waxed and waned.

The other research materials in the collection are works of historical non-fiction, mostly dealing with the period Mantel covered in The Mirror and the Light. During this time, England was under constant threat of invasion from European powers who were hostile to Henry VIII’s break with the Roman church, and Henry VIII’s behaviour was becoming increasingly unpredictable. This period is perhaps more complex and difficult to narrativize than Henry’s marriages, which were the focal point of the first two books in the trilogy. While Mantel left Robertson’s dissertation completely clean, her history books are covered in brightly coloured Post-its with her notes. Most are brief observations on the texts; however, some of them have a literary quality whose tone and style I recognized from the books.

Before I began to study Mantel’s materials, I had not yet read The Mirror and the Light; like many readers, I had become attached to Mantel’s fictionalized Cromwell and was dreading the character’s inevitable downfall. However, my interest was piqued, and I started reading the third instalment. This proved to be a unique reading experience: occasionally, Mantel’s sentences gave me a jolt as I read them, as they were barely changed versions of the notes that I had seen in her research materials. For example, “It is the place we put the tip of our knife, to drive them apart”, affixed to p. 441 of Thomas Wyatt: The Heart’s Forest, is refined to “He has put in the tip of his knife to prise open a gap between the Emperor and François” (The Mirror and the Light, p. 810). Reflecting on the feared attack from the Ottoman Empire, Mantel notes, “Will the Emperor go against the Turks … He will only defend. I can only do what is humanly possible, Charles says” (p. 438). In print, the text reads: “Charles tells him wearily, I am only human … Any season, I must be ready against the Turks” (The Mirror and the Light, pp. 707-8).

These parallels show that Mantel’s research notes reveal more than her command of history; they hold the first sparks of the novels themselves, moments where the finished books took shape. They also are a demonstration of how phrases and sentences came to her almost fully formed, a phenomenon she described in multiple interviews. I had been excited to see into Mantel’s research process, but gaining insight to her creative practice was a true and completely unexpected privilege.

References

Hilary Mantel, The Mirror and the Light, 2020.

Leo Robson, “The Old Consciousness”, The Nation, 22 April 2015.

Mona Simpson, “Hilary Mantel, The Art of Fiction No. 226”, Paris Review, no. 212, Spring 2015.

***

Essays like this remind us why Mantel’s work continues to invite re-reading and discussion. We’d warmly encourage readers to explore Peter Harrington’s bookshop and blog further — it’s a treasure trove for anyone interested in rare books, literary archives, and the material traces of great writers at work. Our thanks again to Emma Anderson for this fascinating glimpse behind the scenes of one of the most important historical novel series of our time.

Website: peterharrington.co.uk

Instagram: peterharringtonrarebooks

Facebook: Peter Harrington

And for those who enjoy conversations about Hilary Mantel, we hope to welcome you to Wolf Hall Weekend 2026, where her work will once again be at the centre of our discussions.

Wolf Hall Weekend by The Tower 2026

Wolf Hall Weekend by The Tower 2026 - Saturday 6th and Sunday 7th June