Guest Interview with Historian, Author and Blogger: Jo Romero

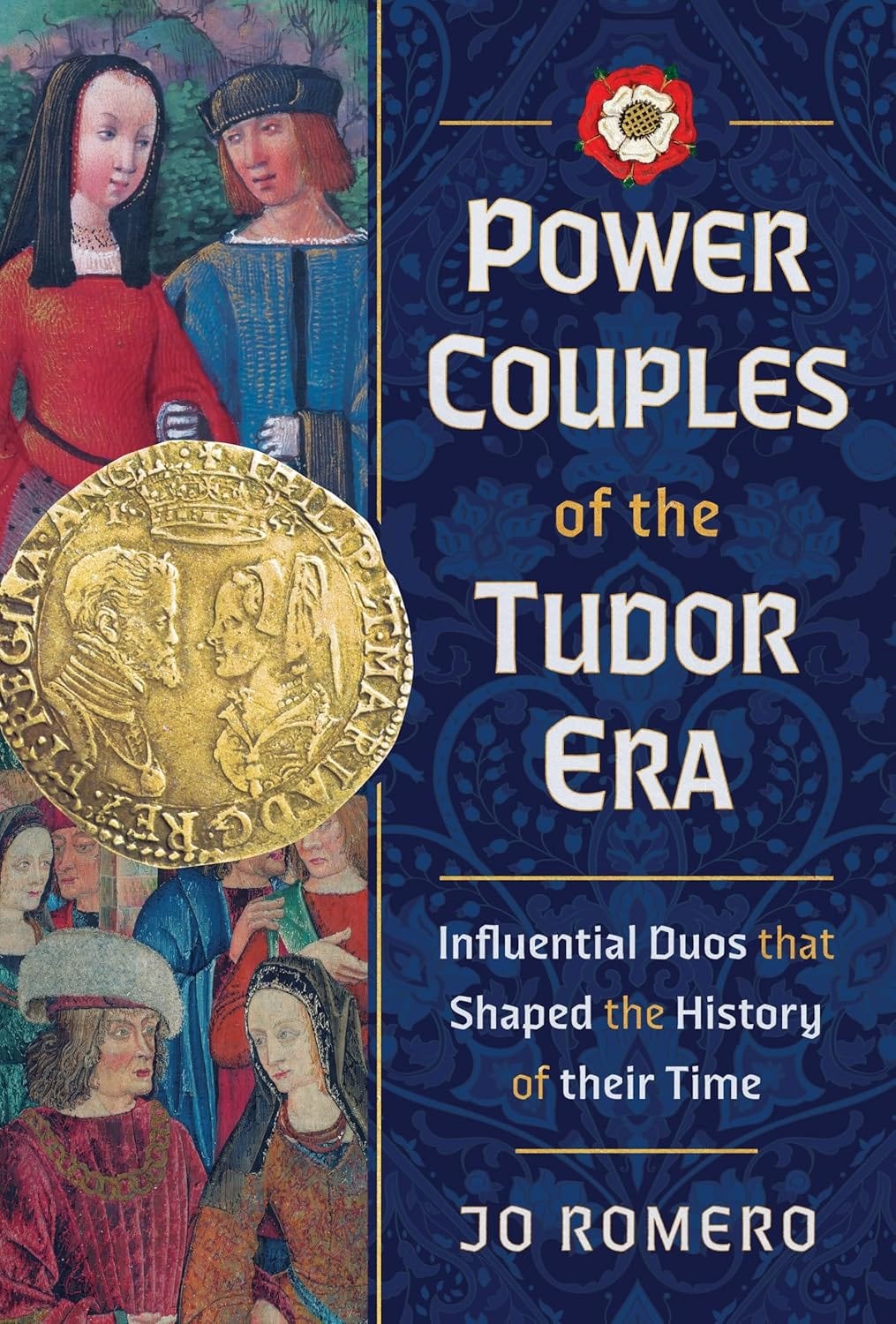

We’re delighted to spotlight the work of Jo Romero who's new book 'Power Couples of the Tudor Era' invites us to rethink the very foundations of Tudor political life.

In ‘Power Couples of the Tudor Era’ (Pen & Sword, 2025) rather than focusing solely on kings, queens, and single actors in isolation, Jo Romero explores how nine couples—from Henry VII and Elizabeth of York to Elizabeth I and Robert Dudley—wielded influence in partnership. These are stories of ambition, alliance, vulnerability, and survival in one of the most dangerous English dynasties in history.

Jo's new book intersects with the world of Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall Trilogy. While Mantel explores the psychological depth and the power play between her characters, Romero brings the historian’s tools to bear—archives, letters, and patterns of patronage—to uncover new insights into how these relationships worked in reality. In the conversation below, Jo reflects on the collaborative nature of Tudor power, the influence of often-overlooked women, and how her findings resonate—or contrast—with Mantel’s unforgettable portrayals.

Jo, Power Couples of the Tudor Era really turns our usual view of Tudor politics on its head. What made you want to look at these stories through the lens of relationships? Did anything surprise you as you began to uncover just how influential these partnerships really were?

Jo: The time period is such an interesting one with so many new developments - the cultural, spiritual and political lives of Tudor residents changed so much over the course of just over a century. But as I looked in more detail at these changes the more I found that they weren't simply the work of individuals as we are so often told, but instead shaped through the efforts of powerful partnerships. Global exploration, new political ideas, religious policy and even personal survival were all manipulated and pushed forward by couples working together. In many cases, this also offered them a greater advantage as they could combine talents, individual influence and personal contacts to increase chances of power and survival.

The most surprising thing though, was learning more about the influence of the lesser-known partner of each pair. Figures like Elizabeth of York, Anne Seymour and Richard Bertie are not always acknowledged for their part in shaping the story of the Tudor age but after a closer look at the sources their contribution is clear.

Even Robert Dudley, who is often viewed today as little more than Elizabeth's handsome courtier (and potential lover), actually enforced real changes to the realm and fulfilled some roles today considered appropriate for a royal consort. Philip of Spain too, was not entirely the absent king of legend but cared about England, its security and future.

Hilary Mantel gives us such a vivid picture of Henry VIII’s marriage to Katherine of Aragon — especially the politics and the heartbreak. How does what you found in the archives compare with Mantel’s fictional portrayal? Was Katherine still pulling political strings even after the marriage began to unravel from the lack of a male heir?

Jo: There was definitely a lot of tension over Katherine's refusal to accept her new, demoted position of Dowager Princess of Wales, and I love Hilary Mantel's portrayal of this, particularly the scene where she meets Thomas Cromwell with her daughter Mary by her side. She is composed but assertive and I feel as if Katherine would have appeared very similar to this. She was the daughter of powerhouse Spanish rulers Isabella and Ferdinand, and was a traditional queen and a fighter. Katherine survived the death of Arthur Tudor, endured years of uncertainty as his widow and then experienced relief when she married Henry VIII in 1509. As his queen, she bore children, presided over a chivalric Renaissance court and defended the country in Henry's absence as regent. For Henry to seek annulment of their marriage in the late 1520s must have been a shock after all she had done for the country, her husband and his kingdom. We can see why she would have refused to agree to the annulment. There were also many people who remained supportive of Katherine in England as well as overseas, and so she was still using her influence through others, such as the Imperial ambassador Chapuys, to try to maintain power and gain support.

Your chapter on Margaret Douglas and Thomas Howard reads like a Tudor Romeo and Juliet — with very real consequences. What drew you to their story? And do you think Mantel hints at Margaret’s quiet power and danger in the Wolf Hall novels?

Margaret Douglas is most often discussed in the context of Elizabeth I's reign, as Mary Queen of Scots' mother-in-law, and so I felt that this earlier chapter in her history was not often explored in depth. I was especially drawn to the way she and Thomas Howard, through their love for one another and their refusal to abandon it, conveyed a different and more subtle power than we generally see in the royal court. Hilary Mantel hints at the couple's power in The Mirror and the Light, having Cromwell suddenly realise that in the spring of 1536 they had been closely monitoring Anne Boleyn, leaving Margaret and Thomas' relationship to flourish completely under the radar. The scenes in the novel where the couple are individually confronted are also powerful, along with the idea that Thomas' brother the Duke of Norfolk might have learned of the affair and kept it hidden to protect future Howard interests. There is definitely evidence that Henry was visibly rattled by Margaret and Thomas Howard's love affair, which left a permanent effect on the realm, threatened the succession and may have even sped up the birth of Henry's successor, Edward VI.

The Courtenays lived at the two extremes of Henry's capricious nature, receiving high royal favour in the early days and execution towards the end. How did Henry Courtenay and Gertrude try to survive that dangerous position? Do you think they were political players, or just caught in the wrong place at the wrong time?

Jo: There is definitely a sense of ambition within Henry and Gertrude's relationship. Henry was the king's cousin on his mother's side, and had a good relationship with Henry VIII as they grew up and as young adults. Gertrude seems to have been the one pushing the couple's agenda in the sources - flitting about the court in disguise and conveying secret and even damaging information to those who could profit from it. She also had a number of secret meetings with Elizabeth Barton, who claimed to be able to pass on messages from God about future events. Later, Barton admitted that she had revealed details about the king's future with both Gertrude and her husband. If we consider Gertrude's position, though, it would have been natural for her to wonder what the future held for her and Henry Courtenay, particularly considering his close proximity to the royal bloodline and Henry VIII's lack of a legal heir in mid-1533. When it all came to light, Henry was enraged, but they sidestepped further punishment by having Gertrude innocently take the blame so that Courtenay could be free of any guilt, and Gertrude could claim she had simply been fooled - and return, cautiously, to favour.

I think the Courtenays began by being political players who wanted to exert power, but the evidence at the time of their fall in 1538 revolves around carelessness rather than a systematic political movement. They had been holding meetings with the Pole family, who were not only well known for their Catholic sympathies but were also cousins of the king on the Yorkist side. There were reports of letters between them being burned, and the group joked about Henry's leg killing him, singing songs about the state of the country. Henry VIII was well aware of the threats to his and Edward's succession and I think by the time he had the Courtenays and their friends in his sights it was too late - the songs, jokes and consultations with Barton just did them no favours.

Let’s talk about Edward and Anne Seymour. Anne in particular is regarded as arrogant, difficult, even ‘monstrous’. But your take is very different. What convinced you she was more of a political powerhouse than a villain? And do you think she was simply ahead of her time?

Jo: Anne was given this kind of assessment in her lifetime and the caricature has endured, in many cases, today. But I think if we could meet her in the modern world we would consider her a good businesswoman or politician. She was somewhat arrogant and proud in nature but the reporting of this was probably exaggerated at the time to fit Tudor beliefs that a woman exerting power was somehow 'unnatural'. Far from being a 'bad wife' as she was once called, she reprimanded her husband's staff, promoted the rise of women in religion and openly helped Edward Seymour's return to power, relying on the couple's contacts and supporters. Anne and Edward shaped changes in politics, administration, religion and literature together, their enemies openly complaining about her influence with her husband while he ruled as Protector. In reality, she was a dedicated wife who worked for her family's public and private success. A touching possession was found among her belongings after her death - she owned a piece of unicorn's horn, which she kept in a purse. Unicorn's horn was believed in the Tudor age to protect against poison, a hint that Anne knew only too well the dangers of a prominent life at the centre of power.

Based on your research, do you think Mantel's portrayal of these Tudor power couples helps us to understand them better or is she seeing them largely through the lens of Thomas Cromwell - with his own power and survival agenda?

Jo: I'm still working my way through The Mirror and the Light, but so far I have loved seeing Hilary Mantel's portrayal of Tudor couples in the novels. The novels take us, through our imagination, deep into the sixteenth century and the gossip, nicknames, humour and danger that existed. If we could visit Tudor England today we would see couples and partnerships at its centre - from the union of kings and queens to the wives of blacksmiths, royal servants and innkeepers, all creating and pushing change on different levels. We see these partnerships in the novels through Cromwell's eyes, but to have them represented in such a realistic and engaging way is not only refreshing, but acknowledges the power they wielded during the era.

Many thanks to Jo for these enlightening reflections that illuminate a central truth echoed in Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall Trilogy: that power in the Tudor world was often shared, negotiated, and fiercely defended through partnership. These themes will form part of our upcoming Wolf Hall Weekend 2026, taking place beside the Tower of London on June 6–7, 2026 where speakers and performers will explore the magnificence and complexity of Mantel’s vision, with an exclusive performance of Mantel and Ben Miles' play adaption of The Mirror and The Light.

Jo’s new book, Power Couples of the Tudor Era, is available now from all major booksellers. You can also join Jo for her official book launch at the Angel Bar in Caversham on the 7th Sept 2025.

Subscribe to Jo Romero’s Substack ‘Love British History’ here:

To book tickets or learn more about the Wolf Hall Weekend programme in June 2026, visit wolfhallweekend.com.

Wolf Hall Weekend by The Tower 2026

Wolf Hall Weekend by The Tower 2026 - Saturday 6th and Sunday 7th June